A few caveats about the Coen Brothers before I write about Inside Llewyen Davis. When I used to teach Film Studies at the University of Calgary, there were two courses that I particularly excelled at: one was my survey of the Coen Brothers, which I taught three times, and which is the closest I’ve come to a class with mythical status (students used to bring their friends to class because “Oh, man, we love Fargo!”). The other was a course on The Big Lebowski, where students would watch that film every week of the term and we’d talk about it every week. I only taught that twice, but at the end of the term the second time the students threw a party and brought all their friends to watch Lebowski together a final time. It was like something out of Community.

What I mean by telling you this is that I have never seen a Coens film that I didn’t like. I’m the guy who thinks Ladykillers is underrated and that Intolerable Cruelty was one of the best films of that year. I can’t do those lists where you rank the Coens films relative to each other because I tend to give them all A+. The combination of the Coens plus Greenwich Village folk scene for Inside Llewyen Davis is, as my friend Donna noted, “quite the collision of overlapping interests” for me.

Between work, the holidays, and an eight year old son, I couldn’t get to Inside Llewyn Davis before last night. I went in expecting it to be the greatest thing ever, and I was not disappointed. I loved every single frame of this film. I wished I could pause it and walk around in it, and look at the copies of Sing Out! on the walls to see which precise ones they were. I wanted to loll in the Gorfein’s apartment and read their books. I wanted to ride in that car. I wanted Llewyn so badly to take that cat.

Watching Inside Llewyn Davis is a lot like reading the first and last chapters of Dylan’s Chronicles. Dylan didn’t have an apartment in New York the first year that he lived there – like Llewyn he couch-surfed, often staying with wealthy patrons like the Gorfeins. Dylan’s full-throated endorsement of serious literature, history and philosophy in that book (and elsewhere) is one of the more convincing arguments I’ve ever read for the canon (essentially: reading the great works of western literature made me the singer I am, you should do it too), and watching Davis pass up those opportunities is the first signal that he’s not going to become Dylan by the end of this film, just as Llewyn visiting his father in the film recalls Dylan’s visits to Guthrie – but Hugh Davis and Woody Guthrie are very different father figures and influences.

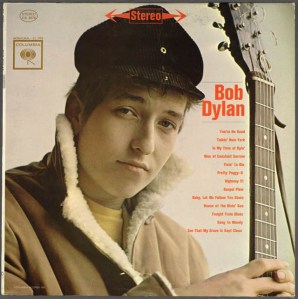

Everything about the film is incredibly well done. The performances are great. The cinematography, which captures that slushy Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan album cover aesthetic so perfectly, is wonderful. The set design and costumes are spot on. At one point Llewyn walks past Kettle of Fish, the bar beside The Gaslight. He never goes in, but just the attention to detail to bother to put that there is remarkable.

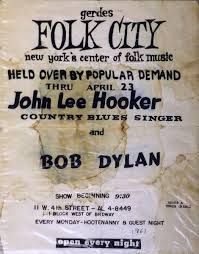

The film uses Dylan, of course, as a counterpoint to Llewyn, as it would have to. Another of the Coens retellings of The Odyssey – the only real question in the film is whether the cat will be revealed as Ulysses or Odysseus – complete with a gate of polished horn, through which one can pass to make your dreams come true, the film develops its travel motifs to the fullest. When Dylan arrives he performs “Farewell”, a song that he recorded on The Witmark Demos in late 1962. It’s one of the many anachronisms that dot the film (the poster for The Incredible Journey is two years too early; The Gaslight didn’t serve alcohol; Dylan didn’t play The Gaslight in early-1961 – indeed, in Chronicles he writes about how difficult it was and how important it was to him to crack that club), but, as with most of the Coens films, it is the anachronisms that give the film its logic (The Incredible Journey poster is maybe the best moment in the entire film).

It has to be Dylan’s Farewell to Llewyn that is his hello to The Gaslight. The lyrics are spot on:

Oh the weather is against me and the wind blows hard

And the rains she’s a-turnin’ into hail

I still might strike it lucky on a highway goin’ west

Though I’m travelling’ on a path beaten trail

So it’s fare thee well my one true love

We’ll meet another day, another time

It ain’t the leavin’

That’s a-greavin’ me

But my true love who’s bound to stay behind

The choice of a Dylan song that is too late for the scene is not an error, of course, it’s just another part of the Dylan myth. If Dylan can lie to Cynthia Gooding about working the carnivals for six years, why can’t the Coens fudge the truth on the time of authorship for one of his songs? Especially when it is in the service of a greater truth?

Llewyn’s true love is the scene that is about to be shaken to its core by the arrival of Dylan, and his pitiable “Au revoir” is the gesture of a defeated man. The Coens build their portrait of the failed artist so economically – how little we know about Llewyn’s former partner Mike, but how clear they make what happened – that we know everything we need to about Llewyn after spending a week with him. It’s a heartbreaking film – more sentimental filmmakers would have milked that final shot for tears – and a convincing portrait of the artist in search of his muse.