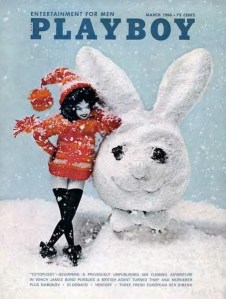

I read it for the articles.

Dylan’s longest interview to date was conducted by Nat Hentoff, jazz critic for the Village Voice, for Playboy in March 1966. It’s surrealist Dylan at his best, or worst if you don’t like it. He says a few things that seem straight, but most of it is bent. It would be a frustrating read for anyone looking for genuine insight into the man. By this point, just before the birth of his first son, Dylan had erected the entire edifice of obstruction around himself. Lies and obstruction had become his calling cards.

Take this exchange:

PLAYBOY: Do you ever think about marrying, settling down, having a home, maybe living abroad? Are there any luxuries you’d like to have, say, a yacht or a Rolls-Royce?

DYLAN: No, I don’t think about those things. If I felt like buying anything, I’d buy it. What you’re asking me about is the future, my future. I’m the last person in the world to ask about my future.

This is a man who was five months married by the time the interview saw print, and already a father of two (Sara, his first wife, had a daughter from a previous relationship). Dylan kept his marriage from his friends – there was no way that he was sharing it with Playboy readers.

The interview, which can be found here, is worth reading in its entirety. Dylan is in a sparring mode with Hentoff (who wrote the liner notes for Freewheelin’). On Hentoff’s first love, jazz Dylan offers this surreal riff:

DYLAN: I mean, what would some parent say to his kid if the kid came home with a glass eye, a Charlie Mingus record and a pocketful of feathers? He’d say, “Who are you following?” And the poor kid would have to stand there with water in his shoes, a bow tie on his ear and soot pouring out of his belly button and say, “Jazz, Father, I’ve been following jazz.”

At other times, Dylan seems to be speaking honestly (or at least you could read him as doing that). His explanation that he was sick of his folk songs is quoted in almost every biography for its truth content:

DYLAN: Anyway, I was playing a lot of songs I didn’t want to play. I was singing words I didn’t really want to sing. I don’t mean words like “God” and “mother” and “President” and “suicide” and “meat cleaver.” I mean simple little words like “if” and “hope” and “you.” But “Like a Rolling Stone” changed it all.

This seems honest and true simply because you can hear it and see it and judge it for yourself in the videos from Newport and in Dont Look Back. It confirms an assumption, a bias that is already built in. On the booing at Newport and Long Island and elsewhere on his fall tour of the United States:

DYLAN: I was kind of stunned. But I can’t put anybody down for coming and booing: after all, they paid to get in. They could have been maybe a little guieter and not so persistent, though. There were a lot of old people there, too; lots of whole families had driven down from Vermont, lots of nurses and their parents, and well, like they just came to hear some relaxing hoedowns, you know, maybe an Indian polka or two. And just when everything’s going all right, here I come on, and the whole place turns into a beer factory. There were a lot of people there who were very pleased that I got booed. I saw them afterward. I do resent somewhat, though, that everybody that booed said they did it because they were old fans.

On his break from topical songs, Dylan is a cross between honest and mysterious. By the end of 1965 Joan Baez had already opened her school for non-violent resistance and had stopped paying her income taxes to protest against American militarism, but Dylan had firmly broken with the cause:

PLAYBOY: Do you think it’s pointless to dedicate yourself to the cause of peace and racial equality?

DYLAN: Not pointless to dedicate yourself to peace and racial equality, but rather, it’s pointless to dedicate yourself to the cause; that’s really pointless. That’s very unknowing. To say “cause of peace” is just like saying “hunk of butter.” I mean, how can you listen to anybody who wants you to believe he’s dedicated to the hunk and not to the butter?

Yet for all that honesty, Dylan could still be confounding, and hilarious.

DYLAN: I do know what my songs are about.

PLAYBOY: And what’s that?

DYLAN: Oh, some are about four minutes; some are about five, and some, believe it or not, are about eleven or twelve.

PLAYBOY: Can’t you be a bit more informative?

DYLAN: Nope.

Poor Nat Hentoff, having to play straight man for all that.

By summer Dylan will have had his motorcycle accident and will retreat from the public eye. After the Royal Albert Hall shows in May (the real ones, not the ones mistakenly labelled as such) there would be no more live performances by Dylan until 1969. Hentoff offers us one of the last glimpses of Dylan before he turns his attention to his family and cuts off the world.